“We reached the mine just in time, for we were hardly in when the fire swept over our trail. I ordered the men to lie face down upon the ground of the tunnel and not dare to sit up unless they wanted to suffocate, for the tunnel was filling with fire gas and smoke. One man tried to make a rush outside, which would have meant certain death. I drew my revolver and said, ‘The next man who tries to leave the tunnel I will shoot.’ "

On August 20th, 1910, high in the Bitterroot Mountains, what later became known as “The Big Blowup” surrounded a group of Forest Service firefighters, trapping them about 10 miles outside of the remote town of Wallace, Idaho. Fortunately, they had forest ranger Edward Pulaski to help lead them to safety.

Edward Pulaski left home at the age of 15 from Green Springs, Ohio to find adventure out West. He dabbled in mining, ranching, and logging before finding himself employed with the U.S. Forest Service in 1908. The forest service was not for the faint of heart. The posting for a Ranger recruitment around that time read:

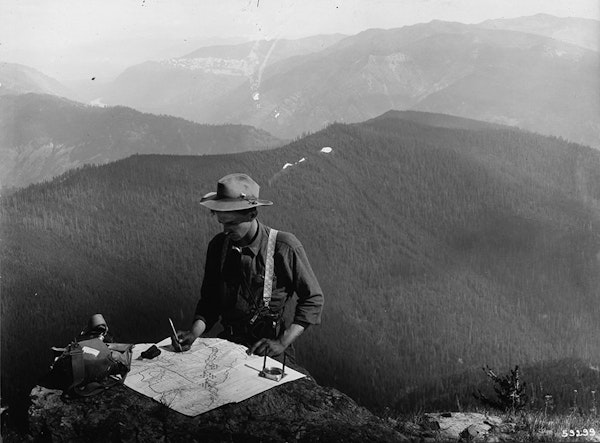

“Men Wanted. A Ranger must be able to take care of himself and his horses under very trying conditions: build trails and cabins; ride all day and all night; pack, shoot, and fight fire without losing his head. All this requires a very vigorous constitution. It means the hardest kind of physical work from beginning to end. It is not a job for those seeking health or light outdoor work…”

Two years later, fires raged all over the nearby mountains. Pulaski later recounted the conditions, “During the summer of 1910 forest fires were everywhere in the Coeur d’ Alene Mountains of northern Idaho. For weeks there had been no rain and the woods were drier than I had ever seen them. The intense heat of the sun, combined with strong winds which sprang up during the day. Served to scatter the fires in all directions. Crews of several hundred men were working twenty-four hours a day throughout the mountains, endeavoring to hold back the fires.

When he left home to head up the mountain he told his wife, “Goodbye I may never see you again.” He knew the conditions were dangerous, but nothing could prepare him for what would happen next.

The 45 men strong crew fought back the fire while gale-force winds caused the fire to surge around them. Pulaski got on his horse and gathered up the crew. Most were unfamiliar with the area and panic-stricken but Pulaski was familiar with the region and knew of an abandoned mine nearby. The sky was darkening all around them even though it was only around noon. He told the men if they listened they might just have a chance of living through the ordeal. He quickly ordered his crew through the forest.

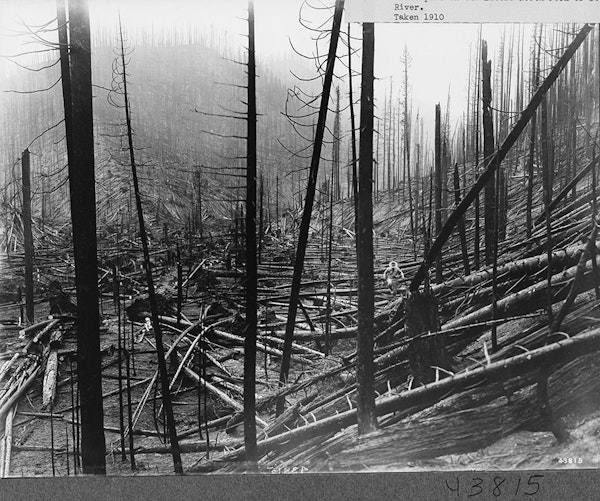

Trees fell all around them, striking and killing a man. They crossed paths with a bear. The bear and the group continued on their ways towards their best guesses at survival. Pulaski led the men into a small abandoned mine as flames swept over the trail behind them.

The mine’s opening measured only six feet high by five feet wide. The tunnel itself was only 250 feet deep. Forty-four men and two horses were now in the cramped tunnel. Hot air and smoke replaced the cold mine air due to the sweltering heat. Pulaski ordered the men to drop to the ground where the air was somewhat breathable. One man tried to make a run for it. Pulaski, sensing panic, pulled his revolver and threatened to shoot the next person that tried to leave. The wood beams at the entrance of the tunnel began to burn. In a last-ditch effort, Pulaski tried dousing the flames with water that pooled on the floor of the mine using his hat as a bucket. He was badly burned in the process. He and his men soon lost consciousness. The situation was growing dire.

At 5 am the next morning a man was heard shouting, “Come outside boys, the boss is dead!” Pulaski replied, “Like hell he is.” The fire had passed through and 39 men survived the night. There was no mention of the horses.

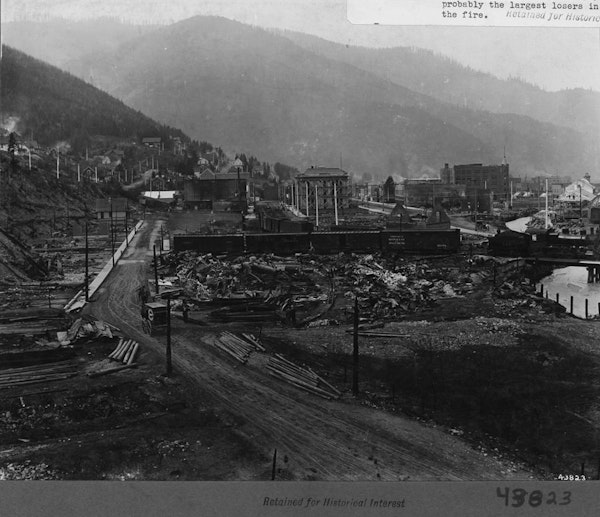

Too weak to walk, the men crawled out of the mine towards the creek with hopes of quenching their thirst. They were very disappointed to find that the water was hot and full of ash. With what little strength they could muster, they headed towards Wallace, making their way through fallen trees, burning logs, and smoke-filled air before reaching the safety of the town.

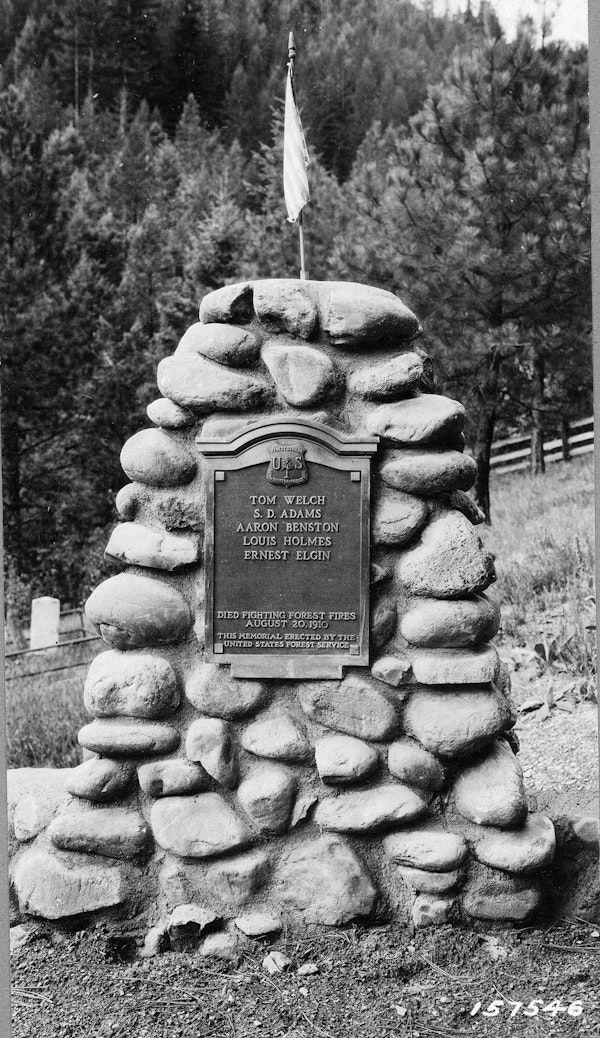

The Great Fire of 1910 burned over three million acres of forest, devastating the region. Seventy-eight firefighters, including the six of Pulaski’s men, died while fighting the fire.

Many of you may have heard the name Pulaski before, even if you have not heard this story. In 1911, Edward Pulaski was credited with the invention of the Pulaski, a combination axe and adze tool that is still widely used by firefighters.

This article is based on US Forest Service signage along the Pulaski Trail. You can hike the trail today if you are in North Idaho. The trail is about 45 minutes east of the Buck Knives factory.

All archival photos: US Forest Service