Based on “The Story of Buck Knives… A Family Business”, written by Tom Ables, we’ll unfold our story, a century of Buck family history and business ventures that created our company.

THE BIRTH OF THE FOLDING HUNTER

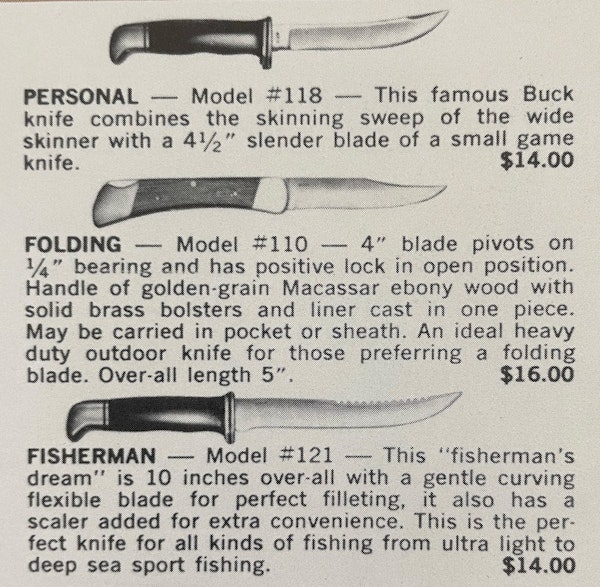

A NEW BOWIE, fish fillet knife, honing kit – these were all steps forward, but they fell far short of the most important decision made by the board in their meeting of April 18, 1963.

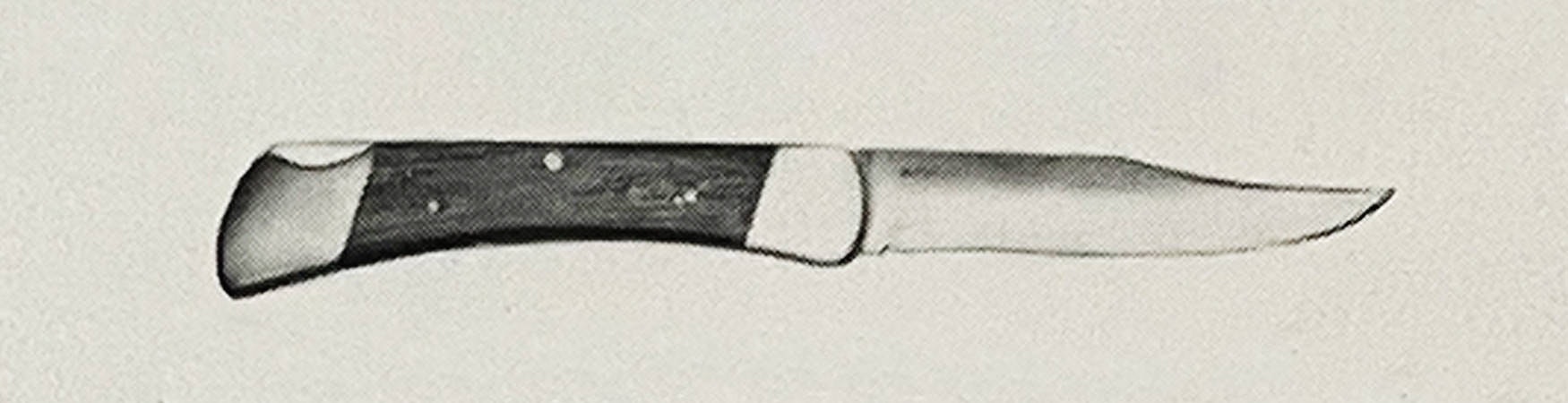

That was the date the board voted to authorize development of a new folding lock blade knife that would become the world-famous Buck Folding Hunter.

There already were some large folding knives on the market that had locking systems. But none had been very successful.

A little first-hand research by the Buck team began to reveal why these knives had not been embraced by the general public.

”We went out and bought three of the rival knives,” Al Buck explained. ”We handled them, used them, tried to get a feel for them. Then we took them apart to see how they worked. In the end, we agreed that all three had features we liked and some features we didn’t like. And we didn’t like the looks of any of them. So we asked one of our engineers if there was a way to get all of the good things into one good-looking knife.”

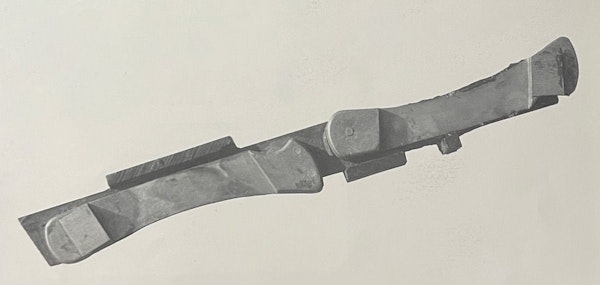

The engineer was Guy Hooser, an eccentric, off-the-wall sort who could do more with baling wire and second-hand scrap iron than most men could do with a fully equipped shop.

There were problems, of course. Since the concept involved a 4-inch blade, a high-tension lock and a low-pressure release, there was little margin for error. The bolsters, handle, pivot pin and release mechanism all presented unique technical challenges.

By mid-summer, however, Hooser had returned to the board with a preliminary model. It was a vast improvement over those being sold by competitors, and on August 8, 1963, the directors approved the basic design. They instructed Hooser to re-configure the handle. They suggested that he incorporate a brass liner. And they asked him to have a second-generation model ready for review in 90 days.

Ironically, the Buck developmental program receiving top priority at the time actually was not the Folding Hunter – it was a new fixed-blade fishing knife.

”We knew it would sell,” Kupilik said. ”We thought the folding knife would be a nice addition to our catalog, but there were serious questions about how successful it would be.”

The new fixed-blade fishing knife was rushed into production in January 1964. The development of the Folding Hunter was far more deliberate.

Additional refinements were needed, and the Buck Folding Hunter did not go into full production until September, meaning only a limited number of units were available for the peak fourth-quarter season of sales.

Al and Chuck Buck, Craig, Ham and Kupilik all shared reservations about their new knife, which became Model 110 in their next catalog. One concern was the overall quality and reliability of the product.

“That first Folding Hunter was not up to our previous standards,” Kupilik confessed. ”We were trying things that had never really been tried before, and not all of them worked just right.

“It took us years to get all of the bugs out of the inner workings of the 110. It became a darned good knife, but it wasn’t in the beginning.”

A second concern was price. The original Folding Hunter carried a price tag of $16.

Finally, since previous lock blades had been left on the shelves, there was no guarantee the public even wanted such a blade, regardless of its price.

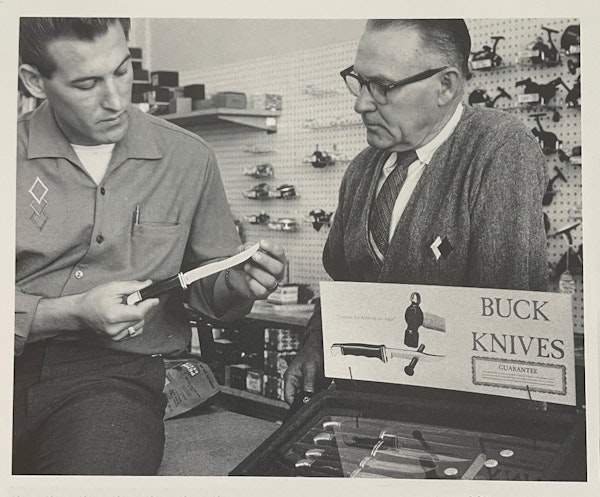

All of these concerns proved groundless. Within six months, the Buck Folding Hunter was the hottest new knife in the industry. And within two years, it was the No. 1 selling sports knife in the world.

Buck Knives probably would have grown and prospered even if the lock blade had not been developed. But there is no question that the Model 110 hastened the process considerable.

The impact the Folding Hunter had on Buck Knives, Inc., is clear when you look at the sales growth in those years.

In 1965, the year Buck introduced the Folding Hunter in its catalog, sales took an immediate jump. And in 1966, sales increased 63%, and then skyrocketed another 60% in 1967.

“We introduced other new products during that period, but the best seller, by far, was the 110, and the spinoff models of the 110, such as the Model 112 Ranger,” Al Buck said.

Their success was not lost on Buck’s competitors. Several quickly introduced their own “knockoff” versions of the Folding Hunter. One of them even used a photograph of the Buck knife in its advertisements.

Clearly, the Model 110 Folding Hunter established Buck Knives as a world leader in the sports knife industry. Not only did the Folding Hunter become the star of the product line overnight, its popularity established the Buck name in the marketplace and boosted sales of other Buck models, too.

To this day, the men responsible believe that God had a hand in directing the company, and they gave Him credit as a full partner in the enterprise.

“We hit with the right knife at the right time and place,” Ham said. “If we had introduced the 110 two years earlier, the name ‘Buck’ would not have been in place. If we had introduced it two years later, the economy would not have supported it. We were fortunate. Our timing was perfect.”

As of January 1, 1991, Buck has sold more than 11 million Folding Hunters, and the Model 110 continues to be the company’s leading seller. Indeed, Buck manufactures about 400,000 lock backs a year, accounting for approximately 20% of all the knives they produce.

Although overshadowed by the dramatic success of the Folding Hunter, Buck’s entry into the basic pocket knife market was a second important factor in the growth of the ‘60s.

Dealers had been asking why Buck Knives didn’t have traditional pocket knives. Actually, serious consideration had been given to that line extension.

“We thought it would be a natural step,” Al Buck said, “but the longer we looked at it, the more we could see the numbers just didn’t add up. At the time, the overriding factor in the sale of pocket knives was price, and we just didn’t feel we could build one at a low enough cost to compete.”

But retailers continued to push for pocket knives to round out the company’s product line, so Buck made a move that opened the door to this large new market. They reached an agreement with Schrade, of New York, under which Buck would purchase pocket knives from Schrade, complete and ready for sale, and market them through Buck retailers.

This arrangement delighted Buck’s sales force, but it troubled Buck executives who prided themselves on the technical excellence of their knives. They were concerned that quality standards would be more difficult to maintain when Buck was not actually manufacturing the knives. Equally troublesome was the fact that the new 300 Series carried the same lifetime warranty that covered other Buck products.

“We wrestled with the pocket knife dilemma for a long time,” Al Buck recalled. “Because the Schrade/Buck knife was competitive price-wise, it was a popular addition to our catalog. However, because the knife was sold by Buck the public expected it to be as reliable as our other knives. That meant backing with our Lifetime Guarantee.”

The problem with backing the guarantee had to do with basic construction. Schrade used “keyhole” type construction, which made it impossible to simply replace the blade of a returned knife.

Concern over the guarantee problem eventually convinced Buck to purchase its pocket knives from the Camillus Knife Co., rather than from Schrade. Camillus utilized solid bolsters in their construction, so Buck could efficiently repair damaged knives under guarantee.

Also included in this new agreement were quality controls designed to enhance the structural quality of the knives. These controls elevated the overall integrity of the Camillus-made Buck 300 Series, but the requirements did lead to friction between Camillus and Buck.

Chuck Buck, whose responsibilities then included the pocket knife program, has reason to recall one case in particular.

“At one point, Camillus expressed concern that our requirements were too stringent,” Buck said. “They were producing knives that never got shipped because they wouldn’t meet our specifications. They were hoping we’d relax the requirements, but we didn’t want to do that.”

“Instead, I offered them $1 for every knife that hadn’t qualified. I thought, ‘After all, how many could he have? I figured there were a couple of thousand, tops. I couldn’t believe it when a truck backed up to our plant one day with 60,000 Camillus/Buck reject knives.”

Clearly, this was not the happiest day in Chuck Buck’s business career. He not only had spent $60,000 in unbudgeted funds, he was now the proud possessor of 60,000 knives which the company couldn’t sell. Bad as it seemed at the time, Chuck recalls that it wasn’t all bad.

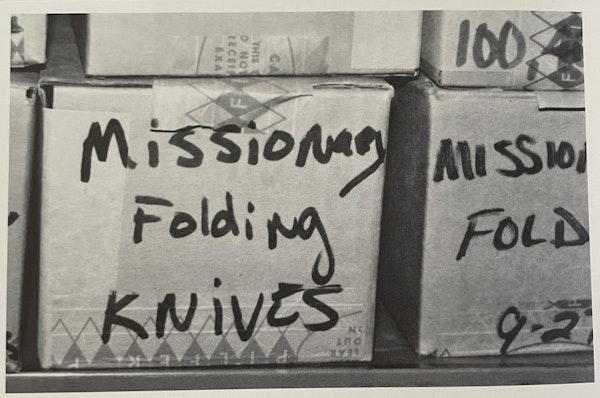

Vern Taylor, Buck’s Northern California sales representative, gave two of these “useless” pocket knives to Christian missionaries. They, in turn, gave them to natives who made good use of them. And Vern shared the idea with Chuck.

“We wound up giving all 60,000 to Christian missionaries and, quite literally, those knives were as good as gold to them,” he said. “In many cases, they were working with people who’d never seen such a knife before. Their definition of quality control’ was a lot different than ours! So the missionaries were able to use those knives like currency.

“For years, I got letters from missionaries asking for more pocket knives. It turned out that the decision to buy them back was not really a mistake after all because we had a part in helping missionaries all over the world as they shared Christ.”

Fueled by the success of the Folding Hunter, and augmented by the line extension provided by the introduction of the 300 Series pocket knives, Buck’s sales increased 950% in the five-year span from 1963 to 1968. In that same time, net profits increased more than 1,000%, and the value of Buck stock soared 900%.