Based on “The Story of Buck Knives… A Family Business”, written by Tom Ables, we’ll unfold our story, a century of Buck family history and business ventures that created our company.

CHAPTER 8: THE CORPORATION’S FIRST STEPS

THE 3,200-SQUARE-FOOT “corporate headquarters” was actually a small Quonset hut in the Old Town district of San Diego. A variety of factors had gone into selection of the site.

It was only two miles from Al Buck’s home on Moreno Boulevard. Its proximity to the Santa Fe rail line provided ready access to the regular shipments of blade forgings from Los Angeles.

And finally, there was the matter of price. It was affordable. The young company was able to procure a 44-month lease, through December 1964, for $135 a month. The state would be clearing the area for the interchange of Interstate Highways 5 and 8, but the Bucks would be able to get started producing knives for four years before moving on.

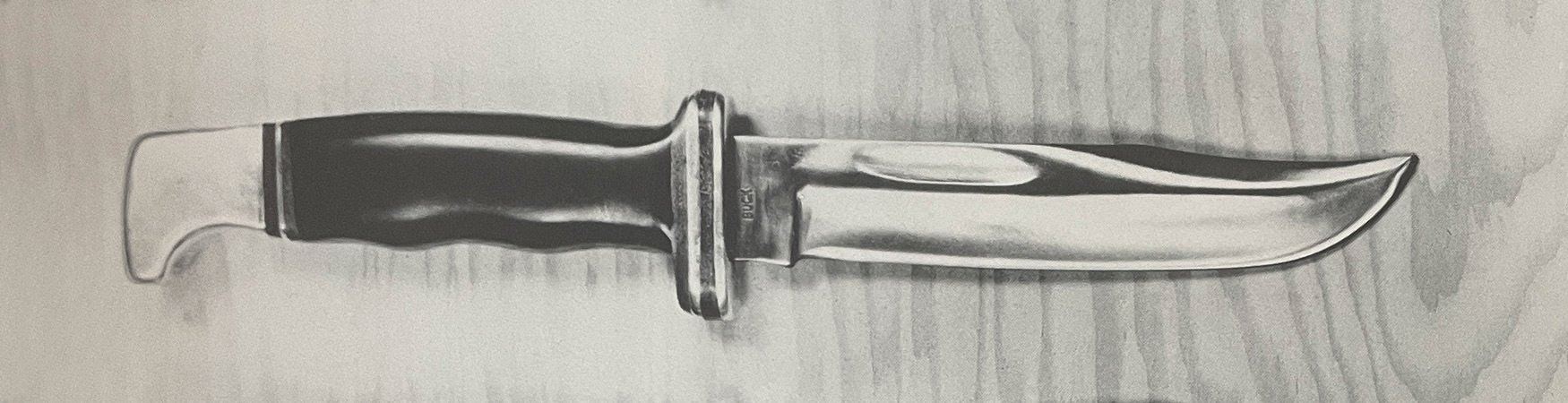

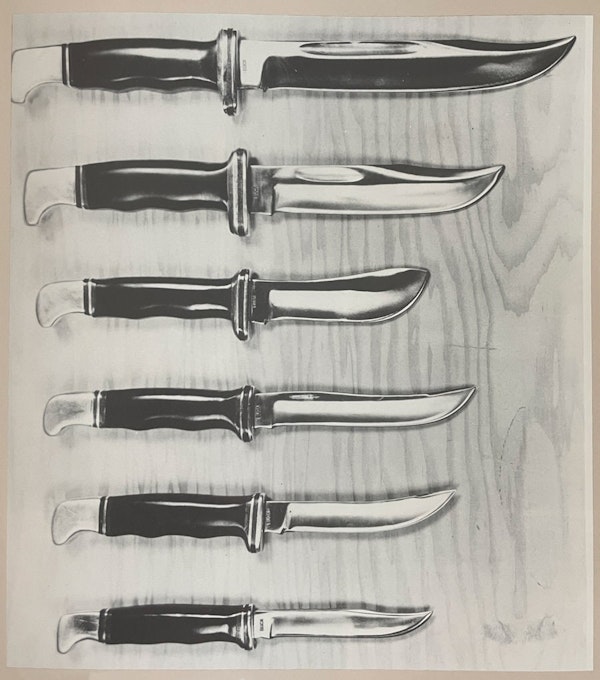

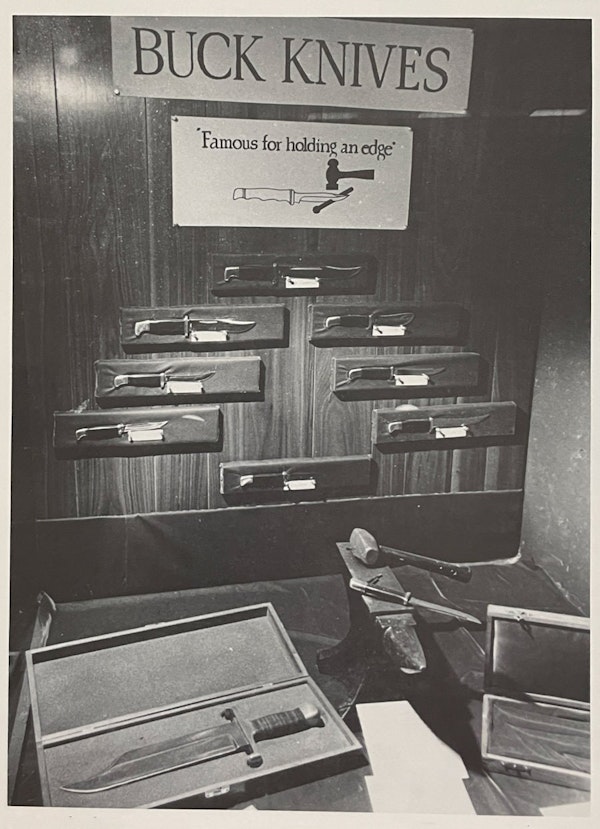

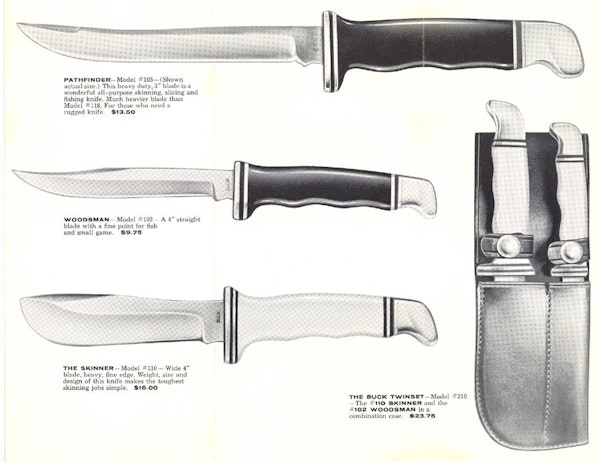

Buck Knives, Inc., began by producing six models of hunting knives, each a black-handled fixed-blade. They were distinguished by two basic features.

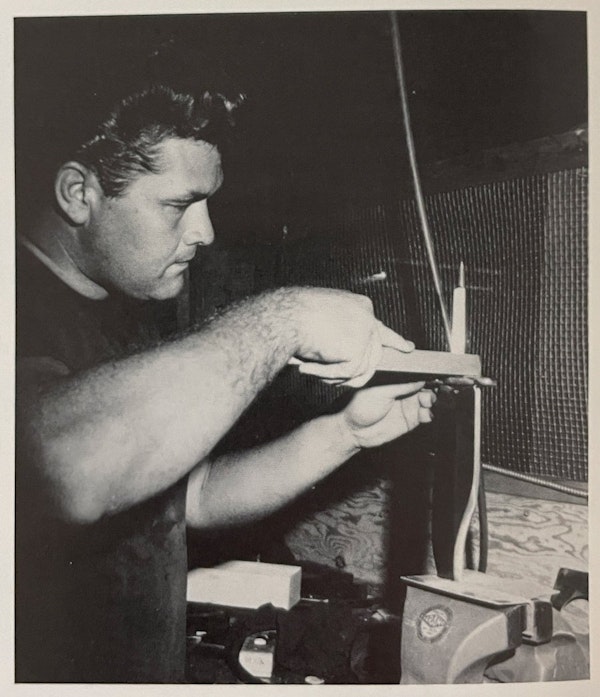

First was the sharpness and durability of the blade, which was crafted from a new, rust-resistant steel alloy, known as 440C. Because this steel included a significant percentage of chrome, it was rust-resistant and had a brighter, cleaner appearance than competing blades. Furthermore, the tempering process Al Buck had learned from his father rendered the blade harder and more durable than blades made by their competitors.

The second most obvious feature of the new Buck knives was their price. In those days, the vast majority of sport knives were priced around $2. Buck’s, by comparison, ranged from $12 to $20.

“For a while there, we were the laughing stock of the industry,” Al Buck recalled. “Our competitors were taking bets on how long we’d last. We were convinced, though, that people would pay additional money to get additional quality. And, eventually, that proved to be true.”

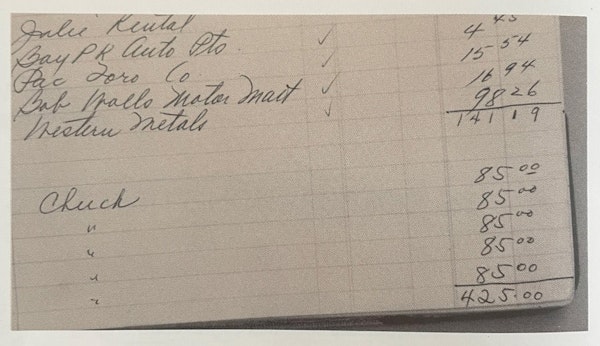

Eventually, it did. But there were some difficult times in the interim. In its first 12 months of operation, the new corporation lost $34,000. Minutes from the board meetings held on September 24, 1962, reveal that Al Buck offered to reduce his salary from $800 a month to $500 a month to lower expenses.

But the board never doubted the long-term potential of the company. The only question was whether or not it could survive long enough to succeed.

The key was to increase the number of independent retailers selling Buck products, and by the spring of 1962 this quest had the president’s undivided attention.

Specifically, it had the undivided personal attention because, in 1962, Al and Ida Buck decided to spend their annual vacation visiting potential dealers. For the better part of two months, they drove their Volkswagen bus from one small town to the next.

“That sales swing by Al really set us apart from the competition,” Kupilik said. “Here is the president of the Buck knife company, Mr. Al Buck himself, walking into the store to chat. On that one long trip, AL showed retailers that we were going to be different from the other major knife companies.”

By the end of 1962, there was a faint glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. Fourth quarter sales had produced net profits totaling $7,000. More than 400 retailers had agreed to sell Buck products. Tooling had begun on several new models.

Significantly, it was then that the board authorized the placement of an ad in “Outdoor Life” magazine, in May 1963.

For whatever reason, knife companies rarely advertised in the 1960s. Schrade did not advertise. Neither did Western or Case. The industry blanched when it learned of Buck’s upcoming advertising “campaign.”

But the small, unpretentious ad program created by Charlie Ramsey, of the Phillips-Ramsey agency, provided vitally important to the growth of Buck Knives. It enabled the Bucks to articulate their principal theme, which was “quality craftsmanship.” This was an important message because it explained why Buck products were more expensive than those of competitors.

A mainstay in Buck’s advertising for many years was a drawing which depicted a Buck knife being driven through a large metal bolt by a blow from a hammer. It was a dramatic way to illustrate the company’s technical excellence.

“The ad wasn’t fancy, not by a long shot, but it really made an impact on the general public,” Al Buck recalled. “At the time, no other knife could cut steel.

“Most manufacturers intentionally made their knives soft, so they could easily be sharpened. We wanted to produce a knife that didn’t need to be sharpened very often,” he said.

“You know, there was a knack to cutting those bolts. Not everyone could do it. But after a while, people began to remember Buck knives as the ones that could actually cut steel! More than anything else, that’s what made us famous.”

Another dramatic innovation was Buck’s Lifetime Guarantee. Confident in the quality of its products, and eager to prove its commitment to service, the company instituted a revolutionary new policy.

Buck Knives agreed to repair or replace, free of charge, any Buck Knife that failed for any reason traced to the manufacturer.

“It was risky, and I think all of us were concerned that people would try to take advantage of us, but the Lifetime Guarantee turned out to be a very good thing,” Al Buck later concluded.

“We were telling people how good our knives were. The guarantee proved we were willing to put our money where our mouths were. Even more important, it kept us on our toes. With that guarantee in effect, we knew we couldn’t afford to produce any second-rate knives. It was the best tool our quality control guys ever had!”

CHAPTER 9: ANOTHER MAJOR TURNING POINT

IN THE SUMMER of 1963, Buck had carved out a small niche in the market, but the seasonal nature of the business – most sports knives at that time were purchased between mid-September and Christmas – had created a cash-flow crisis.

”We were actually in pretty good shape,” Ham recalled with a smile. ”We just didn’t have any money.”

More accurately, the company didn’t have enough money to produce the volume of knives that it felt could be sold in the fall.

This was a major crisis in the history of Buck Knives. Then, a breakthrough which Al Buck remembers vividly.

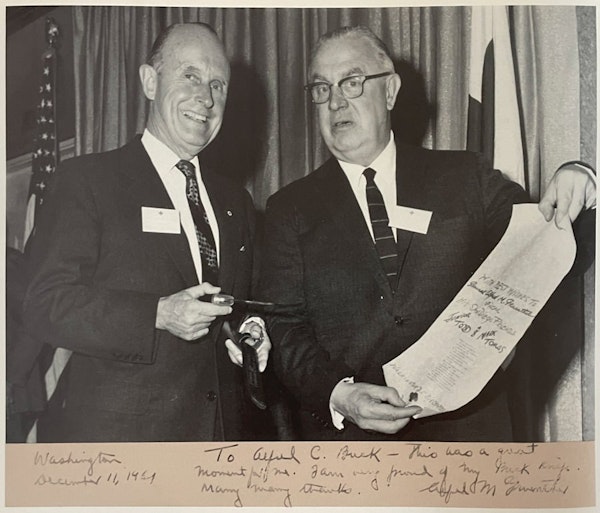

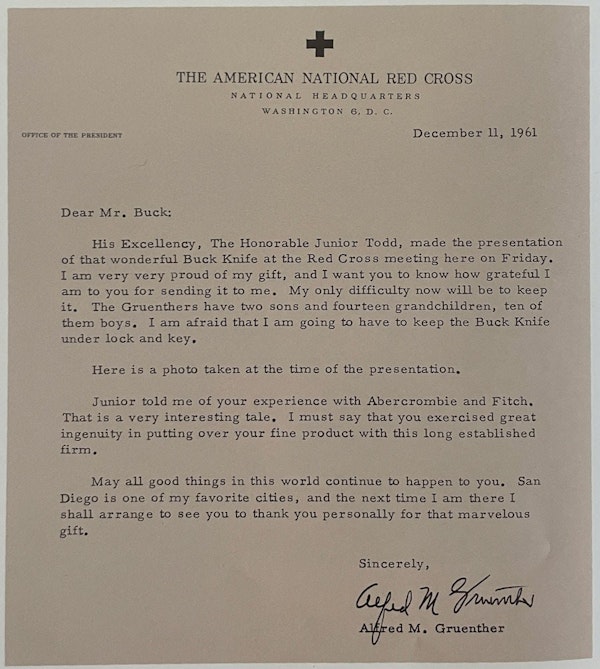

“One night, in the midst of our financial problem, I was praying for guidance, and suddenly my prayers were answered. God brought to my mind the name of a man I barely knew, but a man I knew by reputation.

“His name was O. W. ‘Junior’ Todd, who owned the Stanley Andrews Sporting Goods store in Downtown San Diego. Not only that, he was on the Board of Directors of First National Bank. We didn’t know each other very well, but the very next day I made an appointment to see him,” Buck remembered.

Fortunately, Mr. Todd knew all about Buck Knives. He told Al Buck, “I know your knives and I want to help you; and I want you to meet the president of our bank.”

As a result, the bank loaned money against Buck’s receivables, which solved the short-term problem. But Al Buck got more than that; he got sound advice that led to the company’s next levels of success.

The bank president told Buck that this loan really was little more than a “Band-Aid” and was not to answer to their growth. He urged Buck to go out and sell more stock in the fledgling corporation.

That’s exactly what they did, with a second sale of Buck stock producing $36,500 in new capital.

With the company’s present now secure, and the future looking brighter, the board of directors turned full attention to ways they could realize the firm’s potential. They believed the key to long-range success was an ever evolving line of products.

“As we developed more and more happy customers, we needed to introduce new knives to sell to them the next year, and the year after that,” Ham said.

In the spring of 1963, the board approved the development of a Buck Bowie. A new fishing knife was approved, as was a line of kitchen knives, and a honing kit complete with oil and stone. That honing kit was the first of its kind on the market, but now it’s standard equipment.

Progress was not without its challenges. They designed their innovative new fishing knife with a scaler along the back edge of the blade. It worked great as a scaler, but it also caused a fatiguing action in the steel, and many of those knives had to be replaced. Any still in existence today are a collector’s treasure.

Chuck Buck also recalled the problems they encountered in finding the right container for the highly-penetrating honing oil in the honing kits. Available plastics could not cope with the chemicals in the oil, and standard metal containers with screw-on caps leaked.

Once they solved the problem, the product was off and running.